According to the current Writing Magazine, the latest edition of Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage says it's now acceptable to use 'literally' in a metaphorical sense. So what word does one use when one wants to say that something literally did happen?

No-one is going to think that someone's head literally did explode (unless, I suppose, it's a battlefield scene). But what if someone was literally dancing with rage? Or was literally as white as a sheet? Was he or wasn't he?

I'm currently editing the novel I hope to publish soon, a crime/mystery set in Victorian London. One piece of advice to writers that I've found useful, and am trying to put into practice, is to be sure to extract every last piece of drama and tension from a scene. This obviously doesn't apply if two characters are discussing the case over a cup of tea. But if the heroine is in peril, then give her even more reason to be afraid, make the consequences of failure even more catastrophic. Without, one hopes, tipping over into purple prose and Gothic horror!

I'm also checking that all the small details of the plot hang together. When cutting, or changing the order of scenes and events, it's easy for something to fall through the cracks, so a crucial piece of information wasn't shared when it should have been, or one character tells another about something she has not yet done.

Then it will be one final read through for typos, missing punctuation marks, and so on, before uploading.

Then on to the next one.

My published novels

Monday, 4 May 2015

'His head literally exploded.'

Monday, 16 February 2015

Spring Cleaning

It isn't officially spring for several weeks yet, but here in south east England the first signs are appearing. Snowdrops and crocuses are in flower and daffodils are on their way. On a couple of days it's been warm enough to entice one into the garden to do some pruning and weeding.

On cold wet days there's always something to clear out or tidy up indoors. I've recently been going through some papers which go back decades. I found some cuttings from local newspapers that I evidently found interesting enough to keep at the time.

Now, thirty years later, the advertisements are more interesting than the articles I originally saved.

In 1985 a lady's lambswool sweater cost £17.99. Tweed trousers with turn-ups were £29.99. The great thing about fashion that season, women were told, was the element of choice it offered. Next had four distinct looks; Cross Country, for the independent woman, Dressed for Success for the influential woman, Beatnik Girl for the street look, and Night Club.

Fashion might have been catering for the independent and successful woman, but the toy department sold a 'Housewife Set, complete with brush & pan etc.' for £1.25.

In household fabrics, a single sheet was £6.50. A pair of pillowcases was £3.49. A bath towel was £4.99.

I'm not sure if thirty piece bone china teasets or sets of lead crystal sherry glasses are much in demand in 2015. In 1986 they cost £29.95 and £4.99 respectively from one shop.

The new Renault 11 could be bought for between £5,000 and £6,000 cash, depending on the model.

While many, if not most things, have increased in price over thirty years, others, especially technology and household appliances, have become cheaper, both in relation to incomes and in absolute terms.

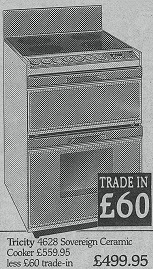

One dealer in electrical appliances had microwave ovens starting at £129. At time of writing, Currys cheapest model is £39.99. A fridge-freezer was £152. Currys current cheapest is £169.99. (Regrettably, Currys choose to spell their name without an apostrophe.)

An automatic washing machine could be had for £159 upwards, a tumble drier from £136. Twin tubs and spin driers were also available.

All these goods could be bought in the High Street, with no need to go to an out of town retail park. And of course, online shopping was unheard of.

Labels:

history: research,

history: social history

Wednesday, 4 February 2015

When is a story not a story?

Short story writing is a specific skill quite separate from novel writing. It is a skill that I do not have, so I've asked my friend Helen Spring to share her thoughts on what makes an effective short story. Helen is a novelist and a short story writer. Her work, including her latest publication, a collection of short stories, is available on Amazon. See what Helen has to say below, and if you agree or disagree with her thoughts, please leave a comment.

WHEN IS A STORY NOT A STORY?

ANSWER: When it is almost any other kind of writing. There must have been more differing opinions written about short stories and their structure than almost any other kind of writing. I have my own opinion about short stories, and when I have voiced it, have received comments which ranged from ‘Utter rubbish!’ to ‘You are so right!’

I think we all have an idea of what a story is, and we always know if we have enjoyed it after reading it. So you may feel I am making a difficulty where there is none. But I can enjoy a piece of writing without agreeing that it is a short story. It may simply be a piece of very good writing describing something which happened – in that case I would call it an anecdote. If it was writing which described something in great detail I might call it an essay. So what does a piece of writing have to have which makes it (in my view) a story?

I believe a story worthy of the name has to have a structure which works through the writing so that the reader has a certain reaction at the end, and knows it is a story. Not necessarily ‘a beginning, a middle and an end,’ although that is a good structure, but something has to change during the narrative to make it into a story.

For example: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but I eventually had a warm coat.’ – That is an anecdote.

But: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but by then I had put on so much weight I couldn’t wear it.’ – That is a story.

P. D. James probably put it best when she argued: ‘A short story does not have to have a plot, but it does have to have a point.’ So many short stories these days (and many of them are published) seem to me to be just an interesting (or not) piece of writing with very little structure.

WHEN IS A STORY NOT A STORY?

ANSWER: When it is almost any other kind of writing. There must have been more differing opinions written about short stories and their structure than almost any other kind of writing. I have my own opinion about short stories, and when I have voiced it, have received comments which ranged from ‘Utter rubbish!’ to ‘You are so right!’

I think we all have an idea of what a story is, and we always know if we have enjoyed it after reading it. So you may feel I am making a difficulty where there is none. But I can enjoy a piece of writing without agreeing that it is a short story. It may simply be a piece of very good writing describing something which happened – in that case I would call it an anecdote. If it was writing which described something in great detail I might call it an essay. So what does a piece of writing have to have which makes it (in my view) a story?

I believe a story worthy of the name has to have a structure which works through the writing so that the reader has a certain reaction at the end, and knows it is a story. Not necessarily ‘a beginning, a middle and an end,’ although that is a good structure, but something has to change during the narrative to make it into a story.

For example: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but I eventually had a warm coat.’ – That is an anecdote.

But: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but by then I had put on so much weight I couldn’t wear it.’ – That is a story.

P. D. James probably put it best when she argued: ‘A short story does not have to have a plot, but it does have to have a point.’ So many short stories these days (and many of them are published) seem to me to be just an interesting (or not) piece of writing with very little structure.

Please don’t think I am advocating some sort of moral message, although earlier short stories often did have them, for example children’s stories (Cinderella, The Three Bears, or Aesop’s fables.) All these have survived so long because they made a point which the reader understood. These days you wouldn’t get far trying to moralise in a story, but the description of actions or thoughts and their consequences (often unforeseen) can make for an interesting and satisfying structure.

If one studies acknowledged masters of the short story, (I am thinking of Guy de Maupassant or the American writer O. Henry, for example) one finds there is always that pivotal point (and sometimes you have to search for it) which turns the process and makes a piece of writing become a story.

I’ll quote as an example the story of Cinderella, simply because it is one we all know. What is the pivotal point in that story which has ensured it lasts forever? If you think about it, it is the loss of Cinderella’s glass slipper as she runs from the ball as the clock chimes midnight. Think about it. If she hadn’t lost the slipper, she would have gone home, all her finery would have disappeared and it would be an anecdote. (‘I went to the ball after all and had a good night out.’) By losing the slipper, the Prince is given the opportunity to find the wearer, which makes possible the ‘happy ever after’.

Often when writing a story, I have found it didn’t quite work, and almost always it is because I have not found that pivotal point which will make the story move, to bring about the satisfying (or horrifying or whatever) ending. This pivotal point does not have to be in any particular place in the story, and it does not have to be an action or event, it can simply be a change in thought processes, but I do believe it has to be there.

Well I’m sure some people disagree with me, and if you do I’d love to hear why you think I’m wrong. When do you think a piece of writing deserves the title ‘STORY’ ?

Helen Spring

If one studies acknowledged masters of the short story, (I am thinking of Guy de Maupassant or the American writer O. Henry, for example) one finds there is always that pivotal point (and sometimes you have to search for it) which turns the process and makes a piece of writing become a story.

I’ll quote as an example the story of Cinderella, simply because it is one we all know. What is the pivotal point in that story which has ensured it lasts forever? If you think about it, it is the loss of Cinderella’s glass slipper as she runs from the ball as the clock chimes midnight. Think about it. If she hadn’t lost the slipper, she would have gone home, all her finery would have disappeared and it would be an anecdote. (‘I went to the ball after all and had a good night out.’) By losing the slipper, the Prince is given the opportunity to find the wearer, which makes possible the ‘happy ever after’.

Often when writing a story, I have found it didn’t quite work, and almost always it is because I have not found that pivotal point which will make the story move, to bring about the satisfying (or horrifying or whatever) ending. This pivotal point does not have to be in any particular place in the story, and it does not have to be an action or event, it can simply be a change in thought processes, but I do believe it has to be there.

Well I’m sure some people disagree with me, and if you do I’d love to hear why you think I’m wrong. When do you think a piece of writing deserves the title ‘STORY’ ?

Helen Spring

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)